The elections to the House of Representatives are approaching. An important, recurring moment in our democratic constitutional state. The basis of democracy is very simple: most votes count. And there are many ways to put this into practice. In the Netherlands, we have opted for a parliamentary democracy in which political parties announce their plans for the coming years, we as citizens are allowed to vote, after which seats in the House are allocated in proportion to the number of votes received. This is followed by a whole process of formation and installation, but we won't go into that in this blog post.

It is very important that this is done properly (controlled, without fraud etc.). After all, decisions about our future are made in the chamber. So if you want to influence future decisions, it's important to let your voice be heard. Simple.

The data management perspective

You could argue that voting has a lot to do with data management. After all, a 'vote' is a data point. It is the record of a citizen's declaration of will to vote for a particular candidate of a particular party in a given election.

In my book on data management and in our courses I take the following position on the link between data quality management and data governance:

- The place where data is created is the only place where you can check the correctness of this data. Correctness is one of the most important quality dimensions of data quality (see for example the website of DAMA-NL for an overview of other quality dimensions).

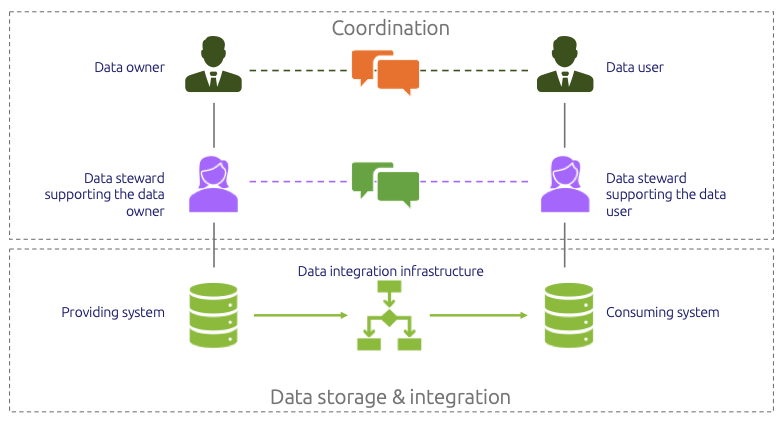

- It is therefore an obvious step to assign responsibility for managing data (and the quality of data) to that location. This is usually linked to the role of a data owner who is supported by data stewards.

- Data does not usually remain stationary in one place; it is also used in other places by data users.

- To ensure that these data users receive the right data of the right quality at the right time, a dialogue on data requirements between owner and user is desirable. This concerns matters such as (a) what data do you need and for what purpose? (b) What should the data look like? (c) What quality requirements do you have for the data? (d) what security requirements are we talking about? Etcetera.

- Based on these requirements the data flow can be designed and realized. Different solutions are possible.

The figure below shows this schematically.

Voting and data management

Traditionally, paper ballots are cast at polling stations in the Netherlands. So you could say: the party responsible for what happens at polling stations is also responsible for the data (on paper) that is created there. This data is counted manually and an official report is made. This is transferred to the mayor after which officials transfer the data to digital systems. That is already a long "journey" for the data.

The fact that elections in the Netherlands are generally conducted without too much fuss suggests that this is okay. To be more precise: apparently we as a society trust that the system of measures taken is sufficient to ensure that the quality of (data processing during) voting and elections is sufficiently well organised to produce reliable election results. Think of measures like the ID-check (are you who you say you are), the fitting out of polling booths to guarantee privacy, and the strict rules about well-sealed ballot boxes.

For years there has been talk of 'other' ways of voting. Digital, for example. Perhaps even from home. The Covid19 crisis has rekindled that discussion. This year, the elderly can vote by post and we all find that very exciting. We find digital voting even more exciting. The discussion generally revolves around aspects such as: to what extent are we able to guarantee that voters are actually who they say they are? How can we ensure that people only vote once? How can we ensure that people are not 'forced' to vote differently than they might wish?

Digital voting could be arranged in different ways, with different sets of measures. Three scenarios are interesting:

- Suppose you replace the paper with a high-security computer in, still, a physical polling station. This would not even have to be connected to a (public) internet connection. Employees of the polling station could still perform the ID check and data could still be transferred to the mayor outside public networks. The big difference is that the data that represents a citizen's vote is immediately digital and no addition errors can occur along that route. This seems to be a risk-avoiding, conservative strategy that can mainly benefit the speed (and partly the reliability) of the process.

- It goes a step further if the voting computers in polling stations communicate directly with central systems through a (secure) online connection. This further increases the speed, but also introduces new risks: online connections can usually be hacked, which could have a direct impact on the quality of the data and thus the election results. The question is whether the extra speed gain outweighs the associated risks.

- It goes a step further if we vote at home, from the comfort of our armchair. You could argue that Digid solutions - whether or not in combination with extra measures - are an excellent way of guaranteeing that a voter is who he says he is. However, there are considerable challenges involved. In addition to issues concerning the security of online connections (and whether or not citizens/voters have secure computers), we must also ask ourselves whether we are not excluding a group of citizens because they lack sufficient digital skills. So here too, the question is whether the benefits outweigh the risks.

Conclusions

It may seem a bit far-fetched, but I would venture the hypothesis: good data management can directly contribute to reliable election results. How this will develop in the future in the light of the digital transformation of our society remains to be seen. Who knows, maybe a Ministry of Digital Affairs will bring a sustainable digital solution closer.